Regardless of the fact that she soon may become one the most powerful and influential women in the most powerful country on Earth, possibly for the next forty years, our ComMedia class has made it known, in no uncertain terms, that they've had it

UP TO HERE!!with Sonia Sotomayor. In fact, if given the choice between another story about SS or a bullet in the head, they would probably say "Umm... How big a bullet?"

So, if that sounds like you, class, you'd better give this entry a skip, because there was

a fascinating article in the

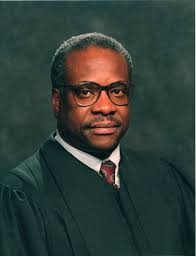

Times last Saturday comparing the life journeys of Ms. Sotomayor and a current sitting Justice, Clarence Thomas.

Okay. Anybody still with me? A couple of fence-sitters, maybe? Try just a little bit. C'mon.

Both come from the humblest of beginnings. Both were members of the first sizable generation of minority students at elite colleges and then Yale Law School. Both benefited from affirmative action policies.

But that is where their similarities end, and their disagreements begin. . .Judge Sotomayor celebrates being Latina, calling it a reason for her success; Justice Thomas bristles at attempts to define him by race and says he has succeeded despite the obstacles it posed. Being a woman of Puerto Rican descent is rich and fulfilling, Judge Sotomayor says, while Justice Thomas calls being a black man in America a largely searing experience. Off the bench, Judge Sotomayor has helped build affirmative action programs. On the bench, Justice Thomas has argued against them with thunderous force.

Wow! How can two people with such similar beginnings end up in such different places?

When Ms. Sotomayor and Mr. Thomas arrived at college — she at Princeton in 1972, he at Holy Cross in 1968 — they worried about the same thing: what others would think when they opened their mouths.

Ms. Sotomayor had grown up in the Bronx speaking Spanish; Mr. Thomas’s relatives in Pin Point, Ga., mixed English with Gullah, a language of the coastal South. Both attended Catholic school, where they were drilled by nuns in grammar and other subjects. But at college, they realized they still sounded unpolished.

Ms. Sotomayor shut herself in her dorm room and eventually resorted to grade-school grammar textbooks to relearn her syntax. Mr. Thomas barely spoke, he said later, and majored in English literature to conquer the language.

“I just worked at it,” he said in an interview years later, “on my pronunciations, sounding out words.”

As affirmative action cases, they were seen as being unworthy of attending their Ivy League schools -- and were made to feel that way.

When the students arrived, they were subject to constant suspicion that they had not earned their slots. “It was a question echoed over and over again, not only verbally but in people’s thoughts,” said Franklin Moore, a former Princeton administrator. Ms. Sotomayor and Mr. Thomas, honors students in high school, considered themselves qualified. But to prove their critics wrong, they studied with special determination.

“We can’t let these people think we just came off the street without anything to offer Princeton,” said Eneida Rosa, another member of the Hispanic contingent, describing how seriously she and Ms. Sotomayor took their studies.

The two future judges led similar student organizations — Mr. Thomas helped found a black student group, while Ms. Sotomayor was co-chairwoman of a Puerto Rican one — and shared the same liberal politics. They graduated at the top of their classes. And afterward, they each headed to Yale Law School.

It wasn't the first time that Clarence Thomas had been made to feel inferior.

Even by the standards of the Jim Crow South, Mr. Thomas’s childhood was marked by bitter blows and isolation. He was taunted not only by classmates at his all-white high school but also by blacks, who called him “ABC,” for “America’s Blackest Child,” on account of his dark skin. A black among Catholics and a Catholic among blacks, he sometimes seemed to fit in nowhere at all.

Mr. Thomas learned he could rely only on himself. His father left when he was a toddler. A few years later, his mother sent him to live with his grandparents, dumping his possessions in grocery bags and sending him out the front door.

Sotomayor's father died when she was nine, and she lived in a very poor neighborhood, but on the whole her childhood was happy.

Ms. Sotomayor also grew up without a father; hers died of heart problems when she was 9. But her mother was a sustaining force, supporting the family by working as a nurse. In a recent speech, Judge Sotomayor recalled her mother and grandmother chatting and chopping ingredients for dinner. “I can’t describe to you the warmth of that moment for a child,” she said. . .

[O]n Princeton’s manicured campus, Ms. Sotomayor explored her roots in a way she never had on trips to Puerto Rico or in “Nuyorican” circles back home. In a Puerto Rican studies seminar, she absorbed the literature, economics, history and politics of the island, and by senior year, she was writing a thesis on its first democratically elected governor. In its dedication, she sounds newly enchanted with her heritage.

“To my family,” she wrote, “for you have given me my Puerto Rican-ness.”

In their college days, it was Sotomayor who worked within the system, and Thomas who was close to being radicalized.

But Ms. Sotomayor was no campus radical. She was more likely to mete out discipline than to be subjected to it: in an early turn at judgeship, she sat on a panel that ruled on student infractions.

William Bowen, Princeton’s president at the time, recalled in an interview that he used to call her for advice on Hispanic issues. After all, the university’s leadership wanted to make it more diverse, and Ms. Sotomayor’s activism helped them make their case. As a result of her efforts, other students said, Princeton hired its first Hispanic administrator and invited a Puerto Rican professor to teach.

While Ms. Sotomayor embraced her ethnicity in college and helped bring more Hispanics to campus, Mr. Thomas began to worry about the consequences of racial categorizations and grew skeptical of Holy Cross’s efforts to enroll blacks.

He flirted a bit with black nationalism, reading Malcolm X’s autobiography until the pages were worn. He drank in Ayn Rand’s ideas about individualism. He identified with the protagonists of Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison novels, whose destinies were determined by racial stereotypes.

“I began to think of myself as a man without a country,” he wrote in his autobiography about his increasing alienation.

Those feelings continued into law school.

Given her standout record at Princeton, said James A. Thomas, a former dean of admissions, Ms. Sotomayor’s background had little role in her acceptance to the school. Again, she immersed herself in Puerto Rican issues. . .

Mr. Thomas, though, felt out of place from the moment he arrived and only became more disaffected. He had listed his race on his application and later felt haunted by the decision.

“I was among the elite, and I knew that no amount of striving could make me one of them,” he wrote. He ran into financial troubles and applied for scholarship money from a wealthy Yale family, a process he found humiliating. Friends recall that he insisted on dressing like a field hand, in overalls and a hat.

Despite their Yale law degrees, both Thomas and Sotomayor had trouble getting jobs.

The problem, Mr. Thomas concluded, was affirmative action. Whites would not hire him, he concluded, because no one believed he had attended Yale on his own merits. He felt acute betrayal: his education was supposed to put him on equal footing, but he was not offered the jobs that his white classmates were getting. He saved the pile of rejection letters, he said in a speech years later.

“It was futile for me to suppose that I could escape the stigmatizing effects of racial preference,” he wrote in his autobiography.

Sonia fought back.

Ms. Sotomayor fought back so intensely — against a Washington firm, now merged with another — that she surprised even some of the school’s Hispanics. She filed a complaint with a faculty-student panel, which rejected the firm’s initial letter of apology and asked for a stronger one. Minority and women’s groups covered campus with fliers supporting her. Ms. Sotomayor eventually dropped her complaint, but the firm had already suffered a blow to its reputation.

Now, I'm not a big fan of Justice Thomas. But don't you think that, when confronted by new and convoluted legal problems, it will be a good think for the Supreme Court to count among its members two judges with such similar and disparate viewpoints? I do.

Ai Weiwei is one of my personal heroes. If you've ever heard of him, it may be as the designer of the "Bird's Nest" Stadium at the Beijing Olympics. Or maybe that exhibition he did in London featuring 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds?

Ai Weiwei is one of my personal heroes. If you've ever heard of him, it may be as the designer of the "Bird's Nest" Stadium at the Beijing Olympics. Or maybe that exhibition he did in London featuring 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds?